Introduction

Recently in a discussion on social media, the subject of ankle dorsiflexion range of motion (DF ROM) and its impact on squat performance was raised. Specifically, it was suggested that squat depth is never limited by ankle DF ROM restrictions, and while ankle DF ROM is commonly blamed, the real culprit for the athlete’s poor form is the coach’s lack of skill to effectively coach the movement.

As this statement drove quite a lot of discussion, this blog post will attempt to address this suggestion and offer my own perspective on this topic.

What does the ankle do during the squat?

Fundamentally, when squatting the ankle alongside the hip and knee function to flex (during the descent) and extend (during the ascent) concurrently to varying degrees to lower and raise the centre of mass. During full squats (defined here as when the hamstrings make full contact with the gastrocnemius musculature) it is expected that the ankle, knee and hip rotate in the sagittal plane through their full available ROM (or at least close to) to achieve full depth.

In a commonly cited study, Hemmerich et al. (1) found that during full squats (unloaded), the ankle joint dorsiflexed to approximately 38.5 ± 5.9°, while the knee and hip joint contributed with 153.7 ± 10.4 and 95.4 ± 26.6 of flexion, respectively. This would suggest that the ankle joint, alongside the proximal segments, is quite important in supporting the performance of a full squat by providing a large percentage of its capacity to dorsiflex. Combine this with evidence that ankle DF ROM (tested with the weight bearing lunge test (WBLT)) is significantly lower in individuals who are unable to perform a full squat (2, 3), I believe a strong case can be made for restrictions in ankle DF ROM being a limiter to squat depth.

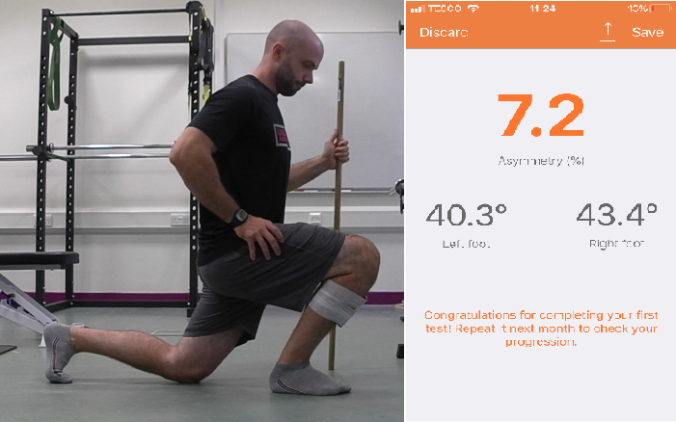

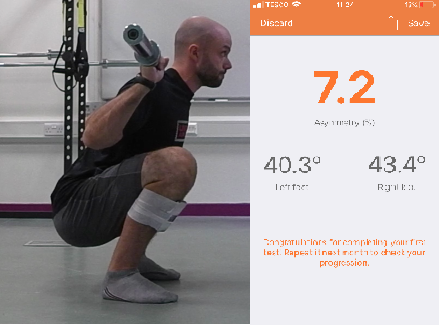

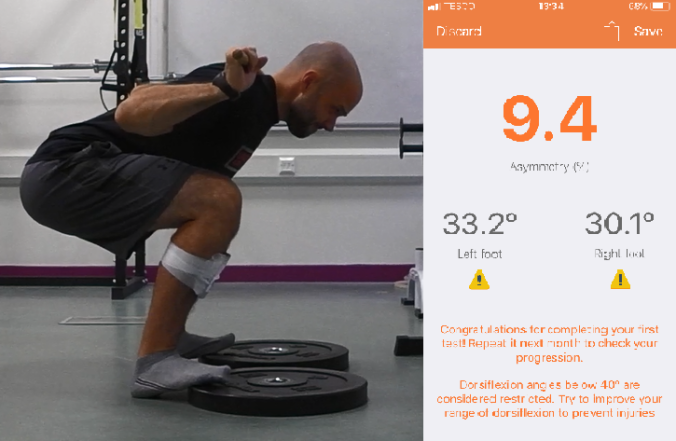

In order to provide visual support for the ankle joints role during squatting, below are images of myself completing a modified weight bearing lunge test (WBLT) (Figure 1), back squat (Figure 2), front squat (Figure 3) and overhead squat (Figure 4). Alongside each figure I’ve screenshot my ankle DF ROM for both ankles during these movements measured using the Dorsiflex app. These values were recorded by taping the phone flat to my tibia (just below the tibial tuberosity), and then squatting and holding the bottom position of the squat variation. Each value represents peak ankle dorsiflexion angle for both the left and right limb. All squats were performed in barefoot with the feet just outside shoulder width apart and slightly externally rotated. Throughout each rep for all of the movements, I’ve done my best to maintain contact with the heel and the ground. *Note: I appreciate there are limitations to this method – I’m just using it to represent a concept.

Figure 1. Modified weight bearing lunge test.

Figure 2. Back squat.

Figure 3. Front squat.

Figure 4. Overhead squat.

My point in presenting these figures is simple: full squatting, irrespective of variation, requires full ankle DF ROM – or at least close to. The modified WBLT in this case represents my full capacity to dorsiflex the ankle. As you can see, dependant on what limb we are testing my ankles achieve a peak dorsiflexion angle of between 40-43° in this test. If we focus on the right ankle, we can see that the peak ankle dorsiflexion score during each squat variation ranges between 41-45°, with the Overhead Squat requiring the most ROM. In fact, the overhead squat produced greater ROM than the modified WBLT, which is most likely due to the modified WBLT being unloaded and the Overhead Squat being loaded.

Throughout my career as both a Strength and Conditioning Coach and as a Lecturer in higher education, I have recorded hundreds of WBLT and scores of <35° are not uncommon. In fact, in a recent data collection, we found a number of individuals with <30° when we strictly controlled for heel lift during the WBLT.

So if <30° of ankle DF ROM is not uncommon, what does a full squat look like when we restrict my ankle DF ROM to 30° during a Back Squat. Figure 5 provides an example of what an athlete may look like with a restriction in ankle DF ROM with the exact same setup position in the back squat as is shown in Figure 2. For obvious reasons, I’ve used a dowel rod here as I didn’t fancy holding the position under load. In this example, the forefoot elevation I’m standing on acts to limit forward rotation of the proximal tibia and imitate an ankle DF ROM restriction. When I attempt to perform a full squat , look what happens to my depth and trunk lean (I promise, I’m doing my best to replicate full depth – check out the face!).

Figure 5. Back squat with artificial restriction to limit ankle dorsiflexion range of motion.

This is not too dissimilar to the athlete in figure 6 who possessed a genuine restriction. This athlete is performing an FMS style Overhead Squat and also possessed an extremely low WBLT score. He also happened to be a national level powerlifter with a back squat well over 2x bodyweight. Clearly his ankle DF ROM restriction showed up in this variation of squat. An important point here is however, that he could still hit parallel with a Low Bar Back Squat during training and competition while maintaining good alignment. As this variation and depth were not restricted by his ankle DF ROM limitation, clearly some variations of squatting can be performed by individuals with reduced ankle mobility.

Figure 6. Bottom position for an athlete with ankle dorsiflexion restriction performing the FMS overhead squat.

Is the ankle joint always to blame?

Absolutely not. In fact, a lot of the time, I’ve found sufficient ankle DF ROM to be present for an athlete to load some variation of the squat pattern to at least a parallel depth while demonstrating an acceptable technique safe for loading. Furthermore, I’ve seen a number of athletes who had sufficient ankle DF ROM but could only reach a half squat position before taking a few steps backward due to loss of balance. In most cases, this is caused by a lack of skill and poor balance in the squat pattern that prevents their full ROM from being displayed. The first time I read about this concept was a few years back in the UKSCA’s Professional Strength and Conditioning Journal in an article titled Squatting is a balance skill: An alternative technical model (4). This article helped to develop the way I viewed movement faults and I highly recommend the read.

Furthermore, restrictions or structural abnormalities at both the knee and hip joints can also create problems in achieving full squat depth. This is illustrated with evidence that individuals with femoroacetabular impingement are unable to squat to the same depth as individuals without hip bone deformity (5).

And this raises another point that builds a lot of individual variation into this equation. What if an ankle restriction is present in someone with a structural restriction at the hip joint? Or someone has poor ankle DF ROM combined with anthropometric dimensions that already require a large trunk lean (i.e. long femurs and short torso)? Or an anteverted hip joint with a concomitant restriction in ankle DF ROM?

This is why absolute statements about what limits or does not limit squat depth are likely unhelpful. Rather, a number of causes can be present that impact the ability to perform a full squat while maintaining acceptable form.

Conclusion

Hopefully this post provides a balanced perspective on what can limit an individual’s ability to perform a full squat. I definitely don’t want to make out that all technical faults in the squat are caused by restrictions in ankle DF ROM, just that they can be caused by mobility deficits.

References

1. Hemmerich, A., Brown, H., Smith, S., Marthandam, S. S. K., & Wyss, U. P. (2006). Hip, knee, and ankle kinematics of high range of motion activities of daily living. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 24(4), 770-781.

2. Kasuyama, T., Sakamoto, M., & Nakazawa, R. (2009). Ankle joint dorsiflexion measurement using the deep squatting posture. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 21(2), 195-199.

3. Rabin, A., & Kozol, Z. (2017). Utility of the overhead squat and forward arm squat in screening for limited ankle dorsiflexion. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(5), 1251-1258.

4. Cleather, D. (2012). Squatting is a balance skill: An alternative technical model. Professional Strength and Conditioning Journal, 25, 17-21.

5. Lamontagne, M., Kennedy, M. J., & Beaulé, P. E. (2009). The effect of cam FAI on hip and pelvic motion during maximum squat. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 467(3), 645-650.